The Rare

Diseases

That Need

Our Attention

Cholestasis

What is Cholestasis?

Cholestasis happens when the flow of bile from the liver is reduced or blocked. Toxic levels of this bile buildup can lead to rare cholestatic liver diseases, including (but not limited to):

- Alagille syndrome (ALGS)2

- Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC)3

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)4

- Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC)4

Patients with cholestatic liver disease typically experience debilitating itching (pruritus) that can lead to scarring, sleep disruption, and significant fatigue, all of which take a significant toll on psychological and social well-being and dramatically impact the quality of life of patients and families. In severe cases, cholestatic liver disease can lead to liver failure and the need for a liver transplant.1

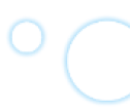

Addressing Cholestasis Through IBAT Inhibition

We are developing two selective inhibitors of the ileal bile acid transporter (also known as IBAT). To better understand how IBAT therapies can help those living with cholestatic liver disease, let’s take a look at how a functioning IBAT system operates.

In a fully functioning system, the body circulates bile acids to help digest food (among other important roles) in the small intestine and then recycles – or transports – them back to the liver.

But for various reasons only partially understood, those who have liver disease experience what we call “cholestasis.”1,2

How IBAT inhibition can help

Our science seeks to help redirect bile acids so that more are excreted in the feces, leading to lower circulating levels and reduced bile buildup in the liver that can lead to damage.

Aiming to Turn Rare Diseases

into Livable Conditions

There is a void of effective therapies for rare cholestatic liver diseases. We believe IBAT therapies can help fill the void, delivering potentially life-changing medicine.

Alagille syndrome (ALGS)

Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC)

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC)

References

- Hilscher MB, Kamath PS, Eaton JE. Cholestatic liver diseases: a primer for generalists and subspecialists. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(10):2263-2279. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.01.015

- Definition & Facts for Alagille Syndrome. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Accessed June 4, 2021. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/liver-disease/alagille-syndrome/definition-facts

- Srivastava A. Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2014;4(1):25-36. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2013.10.005

- Hegade VS, Jones DEJ, Hisrchfield GM. Apical sodium-dependent transporter inhibitors in primary biliary cholangitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Dig Dis. 2017;35(3):267-274. doi:10.1159/000450988

- Fawaz R, Baumann U, Ekong U, et al. Guideline for the evaluation of cholestatic jaundice in infants: joint recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64(1):154-168. doi:10.1097/MPG.0000000000001334

- Data on File. Mirum Pharmaceuticals.

- Alagille syndrome. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Accessed April 29, 2021. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/alagille-syndrome

- Kamath BM, Baker A, Houwen R, Todorova L, Kerkar N. Systematic review: the epidemiology, natural history, and burden of Alagille syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;67(2):148-156. doi:10.1097/MPG.0000000000001958

- Kronsten V, Fitzpatrick E, Baker A. Management of cholestatic pruritus in pediatric patients with Alagille syndrome: the King’s College Hospital experience. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57(2):149-154. doi:10.1097/MPG.0b013e318297e384

- Elisofon SA, Emerick KM, Sinacore JM, Alonso EM. Health status of patients with Alagille syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51(6):759-765. doi:10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181ef3771

- Alagille syndrome. SSM Health. Accessed April 29, 2021. https://www.ssmhealth.com/cardinal-glennon/pediatric-transplant/pediatric-liver-transplant/alagille-syndrome

- Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC). Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Accessed April 29, 2021. https://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/health/p/pfic

- Types and subtypes of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC). Progressive Familial Intrahepatic Cholestasis Advocacy and Resource Network. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://www.pfic.org/types-and-subtypes-of-pfic/

- Progressive familial interhepatic cholestasis. Medline Plus. Accessed April 29, 2021. https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/progressive-familial-intrahepatic-cholestasis/

- Krajnik M, Zylicz Z. Understanding pruritus in systemic disease. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;21(2):151-168. doi:10.1016/S0885-3924(00)00256-6

- Karlsen TH, Folseraas T, Thorburn D, Vesterhus M. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: a comprehensive review. J Hepatol. 2017;67:1298-1323.

- Rupp C, Rössler A, Zhou T, et al. Impact of age at diagnosis on disease progression in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(2):255-262. doi:10.1177/2050640617717156

- Palmela C, Peerani F, Castaneda D, Torres J, Itzkowitz SH. Inflammatory bowel disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis: a review of the phenotype and associated specific features. Gut Liver. 2018;12(1):17-29. doi:10.5009/gnl16510

- Bjøro K, Schrumpf E. Liver transplantation for primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2004;40(4):570-577. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2004.01.021

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis: symptoms, causes, and treatment. American Liver Foundation. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://liverfoundation.org/for-patients/about-the-liver/diseases-of-the-liver/primary-sclerosing-cholangitis/

- Primary biliary cholangitis: symptoms, causes, and treatment. American Liver Foundation. Accessed June 1, 2021. https://liverfoundation.org/for-patients/about-the-liver/diseases-of-the-liver/primary-biliary-cholangitis/

- Primary biliary cholangitis. NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Accessed June 1, 2021. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/primary-biliary-cholangitis/

- Lindor KD, Bowlus CL, Boyer J, Levy C, Mayo M. Primary biliary cholangitis: 2018 practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. Published online November 6, 2018:hep.30145. doi:10.1002/hep.30145

Read about the people

who inspire us